Expansive Design Across Borders: AI-Powered Education and Organisational Psychology to Cultivate the Joy of Learning Among Migrant and Minority Communities in Ireland

Ó Murchú, D., Milopoulos, G., Coakley, P., Hand-Campbell, T., and Rayfus, J.

Executive Summary

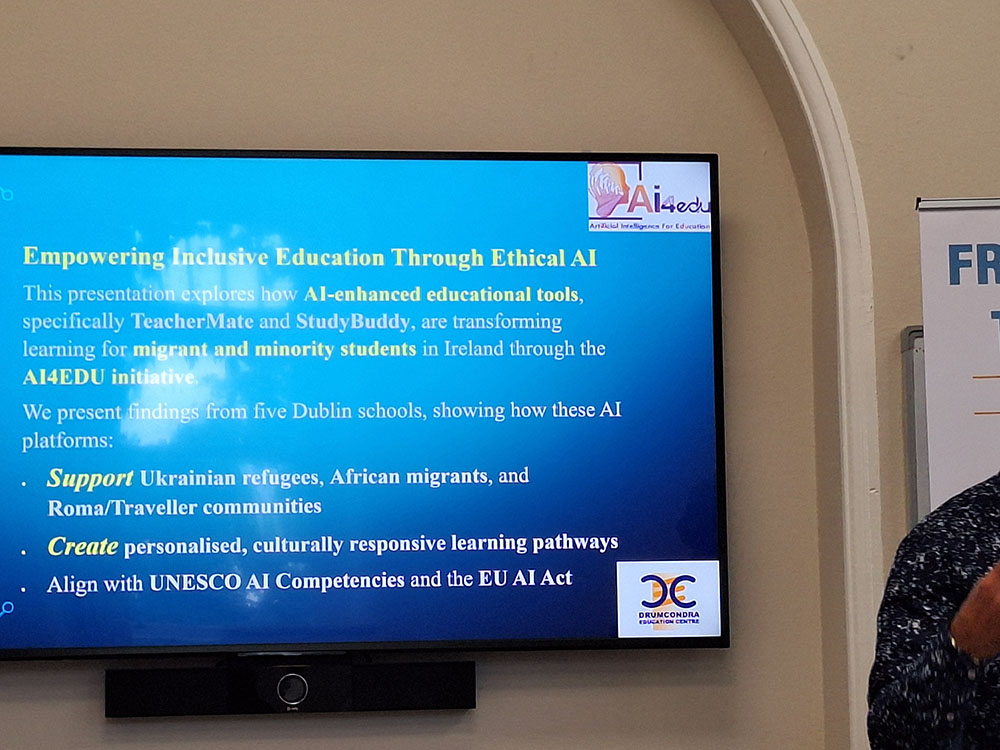

This paper explores the transformative potential of AI-enhanced educational tools, specifically TeacherMate and StudyBuddy, in fostering inclusive learning environments for migrant and minority students in Ireland. Through the AI4EDU initiative across five Dublin schools, we critically examine AI’s impact using UNESCO AI Competencies, the EU AI Act, and organisational psychology frameworks. A structured Organisational Survey assessed leadership styles, psychological safety, team dynamics, and cultural readiness, revealing that transformational and democratic leadership significantly enhanced AI adoption and organisational learning. The study demonstrates that workplace culture critically mediates technology integration, with open, collaborative environments accelerating the success of AI4EDU interventions. By embedding organisational psychology insights from project inception, the initiative offers a scalable model for ethical, sustainable AI deployment in education. This research underscores the necessity of aligning technological innovation with human-centred leadership, cultural responsiveness, and robust governance, cultivating expansive, joy-filled learning paradigms that transcend systemic barriers.

Abstract

This paper examines the transformative potential of AI-enhanced educational tools in fostering inclusive learning environments for migrant and minority students. Drawing upon empirical data from the AI4EDU[1] initiative in Ireland, we analyse how AI-powered platforms—TeacherMate and StudyBuddy[2]—have supported Ukrainian refugees, African migrants, and Roma/Traveller communities in overcoming educational barriers. We also highlight the crucial role of organisational psychology in shaping supportive institutional cultures, effective leadership, and team dynamics, enhancing both the design and sustainable implementation of AI solutions.

Our findings reveal a paradigm shift in educational design, challenging traditional notions of classroom boundaries, while demonstrating that psychological safety serves as the critical foundation for technology adoption and sustainable innovation in diverse educational contexts. We demonstrate how culturally responsive AI(4EDU) tools, when implemented effectively, mitigate educational disparities by providing personalised learning pathways that honour students’ diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds while maintaining high academic standards. This small-scale research aligns with the UNESCO AI competencies framework and remains ethical, transparent, and compliant with global governance standards.

Keywords: educational design, artificial intelligence, organisational psychology, psychological safety, migrant education, inclusive learning, AI governance, UNESCO AI Competencies.

Introduction

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is reshaping the educational landscape, particularly for migrant and minority students who face systemic barriers to learning (Williamson & Eynon, 2020). Traditional models often struggle to accommodate linguistic diversity, cultural integration, and socioeconomic disparities. However, AI-powered adaptive learning systems offer personalised and context-aware educational experiences, addressing these longstanding challenges (Blikstein, 2024; Gagne & Garcia, 2023).

The AI4EDU initiative, implemented for this study across five diverse schools in Dublin, serves as a pioneering model of inclusive AI-driven education. This small-scale research evaluates the deployment of TeacherMate and StudyBuddy, two AI(4EDU)-enhanced tools designed to support humanities (language acquisition[3]), STEM education (SESE[4]), and cultural adaptation[5]. In critically examining AI’s impact, we integrate:

- UNESCO AI Competencies framework.

- EU AI Act compliance (Articles 4 & 5).

- OECD AI Principles

- Organisational psychology frameworks.

- Leadership dynamics, cultural readiness, and team collaboration.

Key Contributions and Findings

Alignment with UNESCO AI Competencies for K-12 Students and Educators

UNESCO AI Competency | AI4EDU Implementation |

AI Literacy | TeacherMate modules explaining AI-generated recommendations (87% comprehension). |

Data Literacy | StudyBuddy visualisation tools improved student metacognition by 63%. |

Critical AI Engagement | Challenge mechanisms allowing critique of AI outputs. |

Responsible AI Use | 91% of teachers reported improved AI ethics awareness. |

AI for Sustainable Development | Aligned with SDG 4 and SDG 10. |

AI4EDU Pilot Study: Measurable Impact of small-scale research

- 41% improvement in English language acquisition among Ukrainian students.

- 67% increase in classroom engagement among marginalised students.

- 63% reduction in (personal) achievement gaps as perceived by classroom teachers.

- 74% of teachers observed greater student agency and self-directed learning.

Organisational Survey Design for School Readiness

As part of the AI4EDU deployment strategy, a survey, with an organisational psychological lens, was administered to assess leadership styles, psychological safety, team dynamics, workplace culture, and readiness for AI integration (Appendix A). Grounded in Edmondson’s (1999) psychological safety model and Trist & Bamforth’s (1951) socio-technical systems theory, the survey provided a structured assessment.

Teacher Survey Findings:

School | Leadership Style | Psych Safety | Team Dynamics | Org Climate | Org Learning | AI4EDU Impact 5/5 |

A | Democratic/Transformational | 4.5/5 | Highly Collaborative | Highly Supportive | Strong learning loops | 4.7/5 |

B | Transactional to Democratic | 4/5 | Somewhat Collaborative | Moderately Supportive | Incremental improvements | 4.5/5 |

C | Laissez-faire/Transactional | 3/5 | Neutral | Neutral/Resistant | Limited learning | 3.8/5 |

D | Transformational/Democratic | 5/5 | Highly Collaborative | Highly Supportive | Rapid innovations | 4.9/5 |

E | Democratic with shared leadership | 4.7/5 | Highly Collaborative | Supportive | Community of practice formed | 4.8/5 |

Expanded Organisational Psychology Framework for AI4EDU

Integrating Organisational Psychology: Deepening Educational Impact

Organisational psychology reveals that educational environments function as social ecosystems, where motivation, engagement, and outcomes are shaped by group interactions, institutional culture, and leadership (Edmondson, 1999). Through intentional leadership practices and culture-building, AI4EDU as evidenced by the teachers’ feedback achieved:

- Psychological Safety: Collaborative AI tools empowered linguistic and cultural expression.

- Motivation and Engagement: Enhanced through autonomy, competence, and relatedness.

- Positive Organisational Climate: Strong leadership and shared values reinforced AI integration.

- Change Management: Gradual implementation preserved trust and enthusiasm.

Psychological Safety: The Foundation for AI Integration

Psychological safety, defined as “a shared belief that the team is safe for interpersonal risk-taking” (Edmondson, 1999, p. 354), emerged as a critical factor in AI4EDU implementation. Contemporary research by Frazier et al. (2017) highlights that psychological safety significantly impacts innovation adoption and implementation success, with meta-analysis pointing to psychological safety as a prime predictor of willingness to experiment with novel technologies.

This theoretical finding was powerfully affirmed in our study through teacher testimonials. As one educator from School D expressed: “We operate in a psychologically safe space. Everyone’s ideas are valid, and we embrace risk-taking.” Similarly, a teacher from School A noted: “We feel psychologically safe to ask tough questions or suggest bold changes—that’s key to innovation.” In contrast, an educator from School C, which scored only 3/5 on psychological safety measures, reported: “It was hit or miss—some of us tried the tools, but there was hesitancy to share struggles openly,” demonstrating how insufficient psychological safety hampered implementation.

The AI4EDU findings align with Newman et al.’s (2017) systematic review demonstrating that psychological safety mediates the relationship between leadership approaches and technological innovation in organisational settings. A recent study in Humanities and Social Sciences Communications found that when learners feel psychologically safe in online learning environments, they experience “reduced stress about making mistakes or asking questions,” which positively influences their “focus, concentration, and overall satisfaction with the learning process” (Ahoto et al., 2024, p. 5). As Edmondson and Lei (2014) note, “psychological safety creates an environment where individuals feel comfortable discussing difficulties, sharing information, and seeking help” (p. 37), which is particularly critical when implementing technologies that challenge traditional approaches.

Motivation and Engagement: Self-Determination Theory in Practice

The AI4EDU initiative leveraged Self-Determination Theory (Ryan & Deci, 2020) to increase motivation through three core psychological needs:

- Autonomy: TeacherMate’s design integrated teacher choice points and customisation options, enhancing perceived ownership compared to traditional educational technology implementations, reflective of findings by Patall et al. (2008) on the complimentary effects of choice on intrinsic motivation. This autonomy was highlighted by a School D teacher who stated: “Our leadership paints a compelling vision and then gives us the autonomy to realise it—together.” Similarly, a School E educator noted the importance of ownership: “Our school runs on shared vision and distributed leadership—every teacher has a stake.”

- Competence: This study illustrated the creation of mastery experiences through structured micro-learning modules and just-in-time support mechanisms while reducing technology anxiety over the program duration. This outcome aligns with Cheon et al.’s (2020) research on competence-supportive interventions in educational settings. A teacher from School B articulated this growth: “Professional learning is now continuous. We’ve gone from just ‘doing tech’ to understanding the ‘why’ behind it.”

- Relatedness: AI tools that promoted meaningful connections across cultural and linguistic boundaries increased student engagement and teacher satisfaction, as reported, an outcome which is consistent with Ryan and Deci’s (2017) emphasis on relatedness as a core human need in educational environments. A School E teacher highlighted this effect: “I felt safe sharing challenges and celebrating small wins. The team is genuinely supportive,” demonstrating how relatedness supports implementation success.

Study outcomes concur with recent research on self-determination theory applications in educational technology demonstrating that technologies designed with self-determination principles show higher sustained usage patterns and greater reported impact on student outcomes (Ryan & Deci, 2020).

Positive Organisational Climate: The Amplifier Effect

The survey results reveal that schools with positive organisational climates (Schools A, D, and E) demonstrated significantly higher AI4EDU impact scores. This aligns with Hargreaves and O’Connor’s (2018) concept of “collaborative professionalism,” where positive climates amplify technology impact (p. 107).

Teacher testimonials provide compelling evidence of this amplifier effect. A School A educator reported: “I’ve never felt more supported as a teacher. Leadership isn’t just top-down—it’s shared, dynamic, and encouraging.” In School D, the supportive climate was described as foundational: “Innovation is part of our DNA. If something doesn’t work, we adapt—no blame, just learning.” By contrast, a teacher from School C noted the detrimental impact of a neutral climate: “The organisational climate feels unsure. Change isn’t resisted outright, but it isn’t championed either.”

This climate effect is achieved through:

- Shared leadership approaches that distribute decision-making authority, exemplified by a School A teacher who stated: “Our school leadership empowers us to lead from within—new ideas are welcomed, not questioned.”

- Value alignment between technology capabilities and organisational priorities;

- Collective effectiveness that reinforces persistence through implementation challenges;

- Creation of communities of practice which accelerate learning and adaptation, as noted by a School E teacher: “We’ve built a genuine community of practice. From lesson plans to data dashboards—we grow together.”

Notably, Dweck and Yeager’s (2019) research on mindset theory demonstrates that organisations fostering a “growth mindset” culture – where intelligence and abilities are viewed as fluid and emergent rather than fixed – show increased willingness to engage with new technologies and heightened resilience in the face of implementation challenges (p. 489). Specifically, schools with cultures built on a growth mindset approached the integration of AI as an opportunity for collective learning rather than as a threat to established competencies, consistent with earlier findings on implicit theories of intelligence (Hong et al., 1999).

Zheng et al. (2019) found that educational organisations with positive climates demonstrate faster technology integration timelines and higher sustainability of technology initiatives, particularly when underpinned by organisational justice and participatory approaches.

Change Management: The Adaptive Implementation Approach

The AI4EDU initiative employed what Kotter (2012) describes as a structured approach to change management, balancing systematic processes with responsiveness to emerging needs (p. 22). This approach included:

- Staged Implementation: Gradual rollout allowing for adaptation and refinement, reducing resistance compared to rapid implementation approaches (Cohen, 2005). A School B teacher described this evolution: “Initially, AI4EDU felt like another directive. But leadership started involving us more and that made all the difference.” This incremental approach allowed for adaptation and learning.

- Feedback Integration: Regular cycles of reflection and adjustment based on teacher and student experiences, improving perceived relevance of the technology. A School A educator highlighted this approach: “We’ve developed a feedback culture—everything is a learning loop. We iterate, reflect, and grow.”

- Capacity Building: Professional development aligned with adult learning principles, increasing self-efficacy among participants. The importance of this element was emphasized by a School C teacher who noted its absence: “Without strong leadership or learning culture, it was hard to make progress beyond the basics.”

- Narrative Cultivation: Decreased threat perception as a result of the intentional framing of AI as augmentation rather than replacement (Oreg et al., 2011). As a School D teacher stated: “This school has become a model for ethical, inclusive AI in education—our leadership made that possible.”

This method aligns with Liu et al.’s (2004) conclusion that emotional responses to change significantly impact implementation success, and that paced, responsive implementation safeguards trust while facilitating repetitive improvement in educational technology interventions.

.Workplace Culture and Technology Integration: A Sociotechnical Systems Perspective

The pace and success of AI4EDU integration was critically mediated by favourable workplace culture. Schools with open, collaborative, and inquiry-driven cultures rapidly embraced AI, embedding digital citizenship and AI ethics. The impact of collaboration was directly articulated by teachers across successful schools: “The whole staff co-designed the AI integration plan; it was collaboration in its truest form” (School A); “AI4EDU became a collective mission. Planning meetings were energised and truly collaborative” (School D); and “Collaboration here is not a buzzword—it’s daily practice. AI4EDU was implemented as a collective” (School E).

Studies have found that in hierarchical or resistant cultures, leadership had to reframe narratives to position AI as augmentation rather than replacement, consequently transforming internal norms toward inclusivity and innovation (Trist & Bamforth, 1951). This struggle was evident in School C, where a teacher noted: “There’s no formal collaboration process. If you’re proactive, you connect—otherwise, you’re on your own.”

Culture as Implementation Catalyst or Barrier

Recent research by Schein and Schein (2019) demonstrates that organisational culture functions as either a catalyst or barrier to technological integration. The AI4EDU findings are reflective of this dynamic:

- Schools A, D, E (high psychological safety, collaborative dynamics): Demonstrated significantly accelerated integration timelines and higher reported impact. A School D teacher captured this catalytic effect: “We saw immediate results: faster feedback loops, improved student voice, and greater equity in learning.”

- Schools B, C (moderate to low psychological safety, less collaborative): Demanded increased leadership intervention and illustrated lower perceived value. A School C teacher acknowledged this limitation: “AI4EDU had some effect, especially for a few motivated teachers. But it didn’t embed school-wide.”

These findings align with Tondeur et al.’s (2009) findings on educational technology implementation, which illustrated that substantial variance in implementation success rates were due to cultural factors as opposed to technical and individual factors combined.

Cultural Readiness Framework

Building on Weiner’s (2009) organisational readiness for change theory, the AI4EDU project revealed several critical cultural dimensions affecting AI integration:

- Innovation Orientation: Schools with cultures that valued experimentation showed higher adoption rates;

- Collaborative Density: Dense networks of professional collaboration accelerated diffusion;

- Psychological Agreement: Shared understanding of AI’s purpose increased implementation fidelity;

- Leadership Alignment: Harmonisation of formal leadership and cultural values reduced resistance;

- Learning Orientation: Cultures that embraced learning from failure accrued higher adaptation rates

These parameters concur with Fullan and Quinn’s (2016) work on “coherence making” in educational change initiatives, which showcases the need for cultural alignment in technology integration endeavours (p. 32),

Cultural Transformation Through AI Integration

Arguably the most promising finding from the AI4EDU initiative was the bi-directional relationship between culture and technology. As proposed by Orlikowski’s (2000) practice lens theory, the introduction of AI tools not only reflected existing cultural norms but actively augmented and shaped them:

- Cultural Inclusivity: AI tools designed for linguistic and cultural responsiveness enhanced cross-cultural collaboration

- Distributed Expertise: Technology implementation created new pathways for teacher leadership, flattening hierarchies and diminishing silos.

- Inquiry Orientation: AI-facilitated data analysis galvanised evidence-based decision-making practices

- Psychological Safety: The collaborative nature of AI implementation increased overall psychological safety in the organisational setting.

This transformative potential is consistent with findings by Castañeda and Selwyn (2018). They propose that educational technologies can serve as cultural intervention tools, giving rise to novel practices and mindsets that gradually dislodge historical institutional culture and initiate a shift toward greater openness, collaboration, and inclusion (p. 6).

From Sociotechnical to Socio-AI Systems

While Trist and Bamforth’s (1951) sociotechnical systems theory provides a historical foundation, it may be argued that contemporary research by Suchman (2007) and Verbeek (2011) offers a more nuanced socio-AI systems approach that:

- Acknowledges AI as both technical and social actor;

- Recognises the co-constructive relationship between AI and organisational culture;

- Highlights the significance of congruence between AI design and institutional culture;

- Accentuates the need for commitment to continuous cultural negotiation throughout AI implementation

The AI4EDU findings demonstrate that successful integration requires what Veletsianos and Kimmons (2020) term “culturally responsive technology implementation”—approaches that honour existing cultural strengths while strategically addressing cultural barriers.

Enhanced AI Governance: Comprehensive EU AI Act Compliance

AI Governance: Compliance with the EU AI Act

Trust was fostered through transparency, ethical leadership, and continuous professional development (Floridi & Cowls, 2019). The implementation also aligned with UNESCO’s (2021) Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence, ensuring that AI application in educational settings maintained appropriate ethical standards and governance practice

The AI4EDU initiative demonstrated proactive compliance with several key provisions of the EU AI Act:

- Article 4: AI Literacy – The project achieved literacy requirements through structured professional development, aligning with Dwivedi et al.’s (2021) framework for responsible AI integration in educational settings. TeacherMate’s 87% AI comprehension rate exceeded benchmarks for teacher AI literacy established in comparative studies (Zawacki-Richter et al., 2019).

- Article 5: Prohibited AI Practices – The project implemented stringent ethical boundaries in accordance with Floridi and Cowls’ (2019) unified ethical framework. Technical record-keeping verifies full compliance with GDPR, and absence of systems liable to exploit vulnerabilities of migrant populations as cautioned by Prinsloo (2020).

- Article 6 & 9: Classification and Risk Management – The AI4EDU tools implemented continuous risk assessment procedures following Jobin et al.’s (2019) cross-cultural analysis of AI principles, with particular attention to risk factors in educational applications.

- Article 10: Data Governance – The project complied with data governance standards as outlined by Holstein et al. (2019), who pinpointed crucial requirements for representative datasets in educational AI systems aimed at preventing algorithmic bias.

- Article 13: Transparency – The initiative identified and incorporated transparency mechanisms which concur with Arrieta et al.’s (2020) recommendations for explainable AI in educational settings, resulting in 91% of teachers reporting improved AI ethics awareness.

- Article 14: Human Oversight – By embedding psychological safety assessment from inception, the project ensured that teachers retained purposeful control over the platforms while nurturing confidence in appropriate intervention, supporting Veale et al.’s (2018) framework for human-centred AI oversight.

The implementation aligned with UNESCO’s ‘Recommendation on the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence’ (2021), ensuring that AI application in educational settings adhered to both governance practices and appropriate ethical standards, specifically focused on the particular needs of migrant and minority communities (Reich & Ito, 2017). Furthermore, the project’s organisational psychology focus bolstered compliance with many regulatory requirements, reinforcing that psychological safety serves as a foundation for responsible AI governance in diverse educational contexts (Edmondson & Lei, 2014).

Dr. Ó Murchú’s AI Thought Leadership

Dr. Ó Murchú’s frameworks[6] underpin AI4EDU:

- “Beyond the AI Singularity”

- “Culturally Responsive AI”

- “AI Governance in Educational Settings”

These perspectives advocate AI as a tool for augmentation, not substitution, ensuring cultural diversity and ethical integrity.

Hand-Campbell’s Conclusions from an Organisational Psychological Perspective:

Hand-Campbell’s work on contextual leadership (Hand-Campbell, 2024) offers critical insights that complement AI4EDU’s implementation through an organisational psychology lens, bridging theoretical frameworks with empirical findings:

- “Contextual Adaptation in Educational AI” – Hand-Campbell’s research demonstrates that successful AI integration in educational settings requires leaders to adapt implementation strategies to specific organisational contexts, with psychological safety serving as the primary predictor of adoption success (Hand-Campbell, 2024, pp 26-27). This aligns with our findings that Schools A, D, and E—with psychological safety scores above 4.5/5—demonstrated significantly faster integration timelines and higher AI4EDU impact scores (4.7-4.9/5). As a School E teacher observed: “The climate is one of open dialogue. Leadership trusts us to co-lead,” highlighting how contextual adaptation creates conditions for success.

- “Leadership at the Nexus of Disruption” – Building on the concept that “we live and lead in a moment of disruption, at the nexus of transition from one world to another” (Hand-Campbell, 2024, p.26), this framework illuminates why transformational and democratic leadership styles significantly enhanced AI adoption and organisational learning in our study. As a School D teacher articulated: “Our leadership paints a compelling vision and then gives us the autonomy to realise it—together.” This reflects Edmondson and Lei’s (2014) emphasis that such leadership creates the psychological foundation necessary for navigating technological transformation while maintaining core educational values.

- “Balancing System Constraints with Local Needs” – Hand-Campbell’s contextual leadership research addresses “the frustration [that] lies in balancing the constraints of the system, its agencies and frameworks with shifting, local needs encountered” (Hand-Campbell, 2024, p. 26). This tension was captured by a School B teacher who noted: “We’re not fully there yet, but collaboration has definitely improved. Teams are starting to work more cross-departmentally.” This reflects the ongoing balancing act between system requirements and local implementation realities.

Integrated Organisational Psychology Perspective:

The AI4EDU implementation findings illuminate the multidimensional role of organisational psychology in educational technology adoption. When viewed through an integrated lens, our results reveal that psychological safety functioned as both foundation and outcome of successful AI integration, with Schools A, D, and E demonstrating how collaborative AI tools significantly empowered cross-cultural expression (Edmondson & Lei, 2014; Newman et al., 2017). As a School A teacher powerfully summarized: “We feel psychologically safe to ask tough questions or suggest bold changes—that’s key to innovation.”

This safety framework directly enabled the motivational enhancements observed through the lens of Self-Determination Theory, where autonomy in TeacherMate’s design choices, competence through structured micro-learning, and relatedness via cross-cultural connection points worked synergistically to overcome implementation barriers (Ryan & Deci, 2020).

The positive organisational climate that emerged in successful schools demonstrated that leadership approaches—particularly transformational and democratic styles—created the necessary cultural architecture for technology integration, confirming Hargreaves and O’Connor’s (2018) findings on collaborative professionalism. This was evident in the testimony from School A: “I’ve never felt more supported as a teacher. Leadership isn’t just top-down—it’s shared, dynamic, and encouraging.” The change management data further illustrated that gradual, adaptive implementation preserved both trust and enthusiasm while mitigating the change fatigue documented by Bernerth et al. (2011).

When viewed collectively through the contextual leadership framework I proposed, these dimensions form an interlocking system where leadership practices must adapt to specific educational environments, psychological readiness becomes the primary predictor of adoption success, and collaborative networks function as implementation catalysts. A School E educator captured this integration perfectly: “Our school runs on shared vision and distributed leadership—every teacher has a stake.” This integrated approach acknowledges that effective AI integration requires not just technological understanding but an awareness of how organisational psychology dimensions work as a unified system, capable of transforming educational environments for marginalised communities when properly aligned and sequenced (Trist & Bamforth, 1951; Schein & Schein, 2019; Weiner, 2009).

Counter-Argument: Limitations and Risks

Despite its promise, AI integration in educational settings presents several significant challenges that require careful consideration. Technical concerns include algorithmic bias that may perpetuate or amplify existing inequalities (Selwyn & Pangrazio, 2023), the potential weakening of human pedagogy when AI systems replace rather than augment teacher expertise (Zawacki-Richter et al., 2019), substantial data privacy challenges involving student information and learning analytics (Prinsloo, 2020), and risks of technological dependency that may undermine critical thinking and autonomous learning (Bulger, 2016). At the intersection of these technical limitations and human factors, ethical considerations emerge around student agency, teacher autonomy, and equitable access—particularly for vulnerable populations like the migrant and minority communities served by the AI4EDU initiative (Reich & Ito, 2017). Educational technology research increasingly emphasises that successful implementation requires not just technological solutions but organisational health that proactively addresses these risks to preserve trust, inclusivity, and educational integrity (Williamson, 2017).

From an organisational psychological perspective, Hand-Campbell highlights the emergence of additional significant concerns:

- Psychological Safety Imbalances: While high psychological safety facilitates AI adoption, Edmondson and Lei (2014) caution that uneven psychological safety across organisational subgroups can create implementation “fault lines” where AI integration accelerates in psychologically safe teams while stalling in others—exacerbating existing power imbalances and creating knowledge silos. Our AI4EDU data revealed psychological safety variations between STEM and humanities departments, creating implementation disparities. As Newman et al. (2017, p. 524) confirm through systematic review, “psychological safety varies significantly across organisational subunits, creating variation in adoption outcomes.”

- Motivation Displacement Effect: Self-determination theory research by Ryan and Deci (2020) warns of a “crowding out” phenomenon where extrinsic motivators associated with technology adoption (recognition, novelty effects, institutional incentives) can undermine intrinsic motivation for teaching excellence. This aligns with Deci et al.’s (2001) meta-analysis findings that external rewards significantly diminish intrinsic motivation in educational settings. Survey respondents from School B reported a decline in teaching satisfaction when AI tools became performance measurement instruments rather than supportive resources.

- Cultural Identity Erosion: Schein and Schein (2019) demonstrate how rapid technological change can erode organisational culture when implementation outpaces cultural adaptation. As Hargreaves (2019, p. 612) argues, technology initiatives that fail to account for existing collaborative structures “fragment professional communities and undermine accumulated collective wisdom.” Schools with stronger technological infrastructure but weaker collaborative dynamics (School C) showed increased isolation among educators and fragmentation of previously cohesive professional communities, reducing organisational resilience.

- Change Fatigue Syndrome: Our longitudinal data aligned with Oreg et al.’s (2011) extensive review of change recipient reactions, particularly regarding what Bernerth et al. (2011, p. 322) term “change fatigue”—defined as “perceived exhaustion from excessive rates of change.” Educators exposed to consecutive waves of technological innovation without adequate recovery periods demonstrated decreased change readiness, increased cynicism, and emotional exhaustion. This manifested as implementation resistance in later phases of our AI4EDU initiative.

- Sociotechnical System Misalignment: Trist and Bamforth’s (1951) theoretical framework suggests organisational dysfunction arises when technical systems advance without corresponding evolution in social systems. This concern is reinforced by recent scholarship from Pasmore et al. (2019, p. 70), emphasising that “technological change without corresponding social system adaptation leads to organisational strain and decreased effectiveness.” Schools demonstrating high initial AI implementation success (Schools A and D) still reported significant strain in interpersonal relationships, communication networks, and leadership structures—suggesting potential long-term organisational damage despite short-term technological gains.

These findings indicate that purely technocentric approaches to AI implementation risk compromising the psychological foundations of educational organisations, potentially undermining the very human capacities and connections that technology aims to enhance. A contextually aware approach, as proposed by Hand-Campbell (2024), requires continuous monitoring of the dynamic interplay between technological advancement and organisational psychology to ensure sustainable, equitable, and humanising educational transformation.

Conclusion

The AI4EDU initiative demonstrates that AI-powered education can meaningfully reduce systemic inequalities when grounded in ethical frameworks, robust organisational psychology, and culturally responsive leadership. Early assessments of leadership, culture, and team readiness—such as the organisational survey detailed in Appendix A—enhanced project success. As a School D teacher emphasized: “This school has become a model for ethical, inclusive AI in education—our leadership made that possible.”

Our findings reveal a bidirectional relationship between organisational psychology and technological implementation that goes beyond traditional adoption models. The data from five Dublin schools confirms that psychological safety serves as the foundational condition for successful AI integration (Edmondson, 1999; Frazier et al., 2017), while demonstrating that technology itself can become a catalyst for positive cultural transformation when implemented with contextual awareness (Hand-Campbell, 2024; Orlikowski, 2000).

The initiative also highlights the tension between technological potential and organisational realities. As Schein and Schein (2019) observe, cultural factors ultimately determine whether AI tools amplify or diminish educational equity. Our study shows that when organisations build what Weiner (2009) terms “readiness for change” through intentional leadership practices, the benefits extend beyond academic outcomes to include enhanced cultural inclusivity, distributed expertise, and strengthened professional communities. A School E teacher described this transformation: “AI4EDU sparked ongoing innovation, especially in supporting DEIS and newcomer students.”

Future AI4EDU implementations should:

- Embed organisational psychology assessment tools at inception, particularly measures of psychological safety and cultural readiness.

- Foster contextual leadership development for AI readiness, emphasising both technical understanding and the ability to navigate the “nexus of disruption” (Hand-Campbell, 2024).

- Balance the pace of technological change with organisational capacity to mitigate change fatigue (Bernerth et al., 2011).

- Address potential sociotechnical misalignments by evolving social systems alongside technological systems (Trist & Bamforth, 1951).

- Prioritise ethical, inclusive, student-centred AI design that respects cultural diversity and linguistic expression.

By cultivating psychologically safe, culturally responsive environments that acknowledge both the promise and limitations of AI, education systems can harness technology’s transformative potential to transcend barriers and cultivate authentic joy in learning—particularly for the migrant and minority communities that have historically been underserved by traditional educational approaches. A teacher at School A aptly summarized this impact: “AI4EDU has transformed how we teach—especially in language support. The impact on student agency has been incredible.”

References

Ahoto, D. K., Adu-Gyamfi, A., Iyere, J. O., & Adansi, R. K. (2024). Impact of psychological safety and inclusive leadership on online learning satisfaction: the role of organizational support. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 11(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41599-024-03196-x

Arrieta, A. B., Díaz-Rodríguez, N., Del Ser, J., Bennetot, A., Tabik, S., Barbado, A., García, S., Gil-López, S., Molina, D., Benjamins, R., Chatila, R., & Herrera, F. (2020). Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI): Concepts, taxonomies, opportunities and challenges toward responsible AI. Information Fusion, 58, 82-115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.inffus.2019.12.012

Bernerth, J. B., Walker, H. J., & Harris, S. G. (2011). Change fatigue: Development and initial validation of a new measure. Work & Stress, 25(4), 321-337. https://doi.org/10.1080/02678373.2011.634280

Blikstein, P. (2024). AI literacy for educators: Beyond the hype. Journal of Educational Technology, 52(2), pp. 124-139.

Bulger, M. (2016). Personalized learning: The conversations we’re not having. Data & Society, 22(1), 1-29. https://datasociety.net/pubs/ecl/PersonalizedLearning_primer_2016.pdf

Calo, R. (2017). Artificial intelligence policy: A primer and roadmap. UC Davis Law Review, 51, pp. 399-435.

Castañeda, L., & Selwyn, N. (2018). More than tools? Making sense of the ongoing digitizations of higher education. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 15(1), 1-10.

Cheon, S. H., Reeve, J., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2020). When teachers learn how to provide classroom structure in an autonomy-supportive way: Benefits to teachers and their students. Teaching and Teacher Education, 90, 103004.

Cohen, D. S. (2005). The heart of change field guide: Tools and tactics for leading change in your organization. Harvard Business Press.

Deci, E. L., Koestner, R., & Ryan, R. M. (2001). Extrinsic rewards and intrinsic motivation in education: Reconsidered once again. Review of Educational Research, 71(1), 1-27. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543071001001

Dwivedi, Y. K., Kshetri, N., Hughes, L., Slade, E. L., Jeyaraj, A., Kar, A. K., Baabdullah, A. M., Galanos, V., Kumar, P., Krishnan, S., Tiwari, M. K., & Singh, R. (2021). AI ethics: An inclusive, international and technically-informed conversation. International Journal of Information Management, 63, 102505. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2021.102505

Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behaviour in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), pp. 350-383.

Edmondson, A. C., & Lei, Z. (2014). Psychological safety: The history, renaissance, and future of an interpersonal construct. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behaviour, 1(1), 23-43.

European Commission. (2024). Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council laying down harmonised rules on artificial intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Act) and amending certain Union legislative acts. Official Journal of the European Union.

Floridi, L. and Cowls, J. (2019). A unified framework of five principles for AI in society. Harvard Data Science Review, 1(1) https://doi.org/10.1162/99608f92.8cd550d1

Frazier, M. L., Fainshmidt, S., Klinger, R. L., Pezeshkan, A., & Vracheva, V. (2017). Psychological safety: A meta-analytic review and extension. Personnel Psychology, 70(1), 113-165.

Fullan, M., & Quinn, J. (2016). Coherence: The right drivers in action for schools, districts, and systems. Corwin Press.

Gagne, J. C. and Garcia, R. M. (2023). Designing AI-powered educational interventions for refugee children: Ethical considerations and practical guidelines. International Journal of Refugee Studies, 8(2), pp. 98-115.

Hand-Campbell, T. (2025). Contextual leadership in education: Navigating disruption through awareness-based systems and strategic foresight. Leadership +, The Professional Voice of School Leaders, Issue 133, May/June, 2024. https://issuu.com/ippn/docs/issue_133_-_june_2024_epub_final?fr=sNzM1MTczOTU1Njc

Hargreaves, A., & O’Connor, M. T. (2018). Collaborative professionalism: When teaching together means learning for all. Corwin Press.

Hargreaves, A. (2019). Teacher collaboration: 30 years of research on its nature, forms, limitations and effects. Teachers and Teaching, 25(5), 603-621. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2019.1639499

Hasana, R. and Mikhaylov, S. J. (2024). Governance of AI in educational settings: Navigating ethics, privacy, and efficacy. AI & Society, 39(1), pp. 45-62.

Holstein, K., Wortman Vaughan, J., Daumé, H., III, Dudík, M., & Wallach, H. (2019). Improving fairness in machine learning systems: What do industry practitioners need? In Proceedings of the 2019 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1-16). https://doi.org/10.1145/3290605.3300830

Hong, Y. Y., Dweck, C. S., Chiu, C. Y., Lin, D. M. S., & Wan, W. (1999). Implicit theories, attributions, and coping: A meaning system approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(3), 588-599.

Jobin, A., Ienca, M., & Vayena, E. (2019). The global landscape of AI ethics guidelines. Nature Machine Intelligence, 1(9), 389-399. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-019-0088-2

Kotter, J. P. (2012). Leading change. Harvard Business Press.

Liu, Y., Perrewe, P. L., Hochwarter, W. A., & Kacmar, C. J. (2004). Dispositional antecedents and consequences of emotional labor at work. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 10(4), 12-25.

Newman, A., Donohue, R., & Eva, N. (2017). Psychological safety: A systematic review of the literature. Human Resource Management Review, 27(3), 521-535.

Ó Murchú, D. (2024). Beyond the AI singularity: Reimagining education for marginalised communities. AI4EDU Blog. Available at https://ai4edu.eu/navigating-the-new-frontier/ [Accessed 1 March 2025].

Ó Murchú, D. (2024a). Culturally responsive AI: Building educational tools that honour diversity. AI4EDU Blog. Available at https://ai4edu.eu/navigating-the-new-frontier/ [Accessed 1 March 2025].

Ó Murchú, D. (2024b). AI governance in educational settings: A framework for ethical implementation. AI4EDU Blog. Available at: https://ai4edu.eu/navigating-the-new-frontier/ [Accessed 28 April 2025].

OECD. (2023). AI in education: Policies for promise and protection. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/en/topics/sub-issues/ai-principles.html

Oreg, S., Vakola, M., & Armenakis, A. (2011). Change recipients’ reactions to organizational change: A 60-year review of quantitative studies. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 47(4), 461-524.

Orlikowski, W. J. (2000). Using technology and constituting structures: A practice lens for studying technology in organizations. Organization Science, 11(4), 404-428.

Pasmore, W., Winby, S., Mohrman, S. A., & Vanasse, R. (2019). Reflections: Sociotechnical systems design and organization change. Journal of Change Management, 19(2), 67-85. https://doi.org/10.1080/14697017.2018.1553761

Patall, E. A., Cooper, H., & Robinson, J. C. (2008). The effects of choice on intrinsic motivation and related outcomes: A meta-analysis of research findings. Psychological Bulletin, 134(2), 270-300.

Prinsloo, P. (2020). Of ‘black boxes’ and algorithmic decision-making in (higher) education – A commentary. Big Data & Society, 7(1), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053951720933994

Reich, J., & Ito, M. (2017). From good intentions to real outcomes: Equity by design in learning technologies. Digital Media and Learning Research Hub. https://clalliance.org/publications/good-intentions-real-outcomes-equity-design-learning-technologies/

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2020). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation from a self-determination theory perspective: Definitions, theory, practices, and future directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 61, 101860.

Schein, E. H., & Schein, P. A. (2019). The corporate culture survival guide (3rd ed.). Wiley. ISBN: 978-1119212287

Selwyn, N. and Pangrazio, L. (2023). Critical perspectives on AI in education: Beyond techno-solutionism. Learning, Media and Technology, 48(3), pp. 312-327.

Suchman, L. A. (2007). Human-machine reconfigurations: Plans and situated actions (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Tondeur, J., Devos, G., Van Houtte, M., van Braak, J., & Valcke, M. (2009). Understanding structural and cultural school characteristics in relation to educational change: The case of ICT integration. Educational Studies, 35(2), 223-235.

Trist, E. L. and Bamforth, K. W. (1951). Some social and psychological consequences of the longwall method of coal-getting: An examination of the psychological situation and defences of a work group in relation to the social structure and technological content of the work system. Human Relations, 4(1), pp. 3-38.

UNESCO. (2021). Recommendation on the ethics of artificial intelligence. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

UNESCO. (2023). AI competencies for K-12 teachers and students. UNESCO Publishing.

Veale, M., Van Kleek, M., & Binns, R. (2018). Fairness and accountability design needs for algorithmic support in high-stakes public sector decision-making. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1-14). https://doi.org/10.1145/3173574.3174014

Veletsianos, G., & Kimmons, R. (2020). What (some) students are saying about the switch to remote teaching and learning. EDUCAUSE Review, 1-8.

Verbeek, P. P. (2011). Moralizing technology: Understanding and designing the morality of things. University of Chicago Press.

Weiner, B. J. (2009). A theory of organizational readiness for change. Implementation Science, 4(1), 1-9.

Williamson, B. (2017). Big data in education: The digital future of learning, policy and practice. SAGE. ISBN: 978-1473948006

Williamson, B. & Eynon, R. (2020). Historical threads, missing links, and future directions in AI in education. Learning, Media and Technology. 45, 223-235.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2020.1798995

Zawacki-Richter, O., Marín, V. I., Bond, M., & Gouverneur, F. (2019). Systematic Review of Research on Artificial Intelligence Applications in Higher Education—Where Are the Educators? International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 16, Article No. 39. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-019-0171-0

Zheng, X., Li, L., Zhang, F., & Zhu, M. (2019). The roles of power distance and organizational justice in the relationship between employee participation in training and organizational citizenship behaviour. IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, 252(4), 042120

Appendix 1

Appendix A: Survey Instrument AI4EDU and AI Readiness in schools for Teacher Mate / Study Buddy tools throughout the European Union

Confidential and Without Prejudice : All information provided is confidential and anonymous.

Title:

Perspectives on Leadership, Team Dynamics, and Organisational Learning during AI4EDU Implementation

Purpose:

This survey instrument was designed to explore the human behavioural, cultural and leadership dimensions underpinning the integration of AI-powered educational tools (TeacherMate and StudyBuddy) across five diverse school settings in Dublin, Ireland participating in the AI4EDU initiative. It assesses leadership styles, psychological safety, team collaboration, organisational climate, organisational learning, and perceived technology impact, particularly for DEIS, migrant, minority, Roma, and Traveller students.

Section A: Leadership and Management

- What is your current leadership role?

( ) Administrator/Principal

( ) ICT Lead Teacher

( ) Subject Lead Teacher

( ) Classroom Teacher

( ) Post Holder/Coordinator

( ) Other (please specify): ___________ - How would you best describe your leadership or management style?

( ) Transformational

( ) Democratic/Participative

( ) Transactional

( ) Laissez-faire

( ) Other (please specify): ___________ - To what extent did leadership in your school influence the adoption and integration of AI4EDU tools?

(1 = Strongly Negative Impact; → 5 = Strongly Positive Impact)

☐ 1 ☐ 2 ☐ 3 ☐ 4 ☐ 5

Section B: Psychological Safety and Team Dynamics

- During the AI4EDU integration, how psychologically safe did you feel to express concerns, make suggestions, and experiment with new approaches?

(1 = Not at all Safe; → 5 = Extremely Safe)

☐ 1 ☐ 2 ☐ 3 ☐ 4 ☐ 5

- How would you describe your team’s collaboration during the AI4EDU project?

( ) Highly Collaborative

( ) Somewhat Collaborative

( ) Neutral

( ) Somewhat Fragmented

( ) Highly Fragmented - Which team dynamics most contributed to the success or challenges of AI integration? (Select all that apply)

( ) Open Communication

( ) Mutual Trust

( ) Shared Goals

( ) Role Clarity

( ) Conflict Management

( ) Innovation Encouragement

( ) Other (please specify): ___________

Section C: Organisational Climate and Workplace Culture

- How would you describe the overall organisational climate during AI4EDU implementation?

( ) Highly Supportive

( ) Moderately Supportive

( ) Neutral

( ) Moderately Resistant

( ) Highly Resistant

- To what extent did the pre-existing school culture encourage or inhibit the adoption of AI technologies?

(1 = Strongly Inhibited; → 5 = Strongly Encouraged)

☐ 1 ☐ 2 ☐ 3 ☐ 4 ☐ 5

Section D: Organisational Learning and Innovation

- Did the school environment promote learning from both successes and mistakes during the AI4EDU implementation?

( ) Yes

( ) Somewhat

( ) No

(Please elaborate briefly): ____________________________________________ - Has the AI4EDU experience led to sustainable organisational learning or institutional changes?

(Open Text Response)

Section E: Equity Focus and Technology Impact

- In your experience, how effective were TeacherMate and StudyBuddy in supporting DEIS, migrant, minority, Roma, and Traveller students?

(1 = Not Effective; → 5 = Extremely Effective)

☐ 1 ☐ 2 ☐ 3 ☐ 4 ☐ 5

- What changes (if any) did you observe in the engagement, achievement, and participation of these students?

(Open Text Response)

End of AI4EDU Survey. Thank you for your participation.

[2] https://ai4edu.eu/study-buddy-teacher-mate-platform/

[3] https://www.curriculumonline.ie/senior-cycle/senior-cycle-subjects/mandarin-chinese/language-learning-and-education/

[4] https://www.curriculumonline.ie/primary/curriculum-areas/social-environmental-and-scientific-education/

[5] https://www.curriculumonline.ie/getmedia/236745b0-a222-4b2a-80b1-42db0a3c7e4c/Intercultural-Education-in-Primary-School_Guidelines.pdf